The stories included here are excerpted from Nityananda: In Divine Presence, by Swami Chetanananda and Captain M.U. Hatengdi, published by Rudra Press. The book is a collection of stories gathered from devotees of Nityananda or their families. They demonstrate some of the unusual qualities of Nityananda, as observed by those who were closest to him during his life.

As Swami Chetanananda, founder of The Movement Center, writes in the Foreword:

I had the good fortune in India to hear many stories about Nityananda--stories that reflected his simplicity, his austerity, his detachment from the world, and his pure and powerful love for those who came to him. The more I heard, the more I recognized two things. First of all, they deserved a larger audience. Secondly, these stories were the most powerful and direct way to express the essence of hisvery extraordinary presence. I decided to gather as many stories as I could, and began to travel along the route that Nityananda followed--from Cannanore in the south, through Mangalore and Kanhangad, and finally to Ganeshpuri. Along the way, I met many people who had known him directly or whose parents had known him. Their remarkable and moving narratives confirmed my sense of what an exceptional being Nityananda was as well as how rich a collection of stories about him would be.

AT THE PALANI TEMPLE

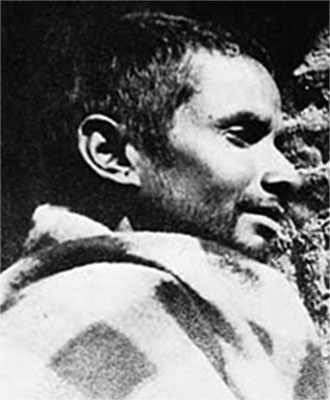

One of the few authenticated stories from the time before Nityananda settled in Ganeshpuri takes place at the Palani Temple. There Lord Subramanya, a brother of Lord Ganesh in Hindu mythology, is the presiding deity. In those days, Nityananda looked like an eccentric wanderer, his wire-thin body healthy and glowing. Late one morning he was ascending the last few steps to the shrine when the attendant priest, having just locked the doors after morning worship, was descending. Nityananda asked him to re-open the doors and wave a ritual light and incense (arati) before the deity. Astonished that a vagrant would dare make such a request, the priest curtly told Nityananda that the time for morning worship was over.

Nityananda continued on. The priest, expecting him to walk around the shrine and worship at the Muslim altar in the back, was not concerned until he heard the temple bells ringing. Turning, he was astonished to see the doors open, Nityananda sitting in the deity’s place, and arati being waved before him by invisible hands. The vision vanished at once, and Nityananda left the shrine to stand on one leg for some time, steadily gazing upward. Coins poured at his feet, offered, some say, by pilgrims, while others say by an unseen source. In any case, he was accorded all the honors of a Master. When the surrounding pilgrims begged him to stay, he refused and instructed them to use the money to provide a daily meal of rice porridge to visiting renunciates. It was later learned that local sannyasis had been praying for this very thing.

Leaving the Pantalayani area, the young Master encountered an errant gang of youths in Cannanore. One of them wrapped a kerosene-soaked rag on the Master’s left hand and set it ablaze. Nityananda didn’t resist physically but instead transferred the burning sensation to the one who had attacked him. Crying out in pain, the unexpected victim begged for mercy. As Nityananda extinguished the fire on his own hand, the sensation in the other’s subsided. Years later, he explained to devotees:

Those with inner wisdom (jnanis) do not go in for miracles. However, this does not mean that a burning rag tied to their hands does not hurt. They suffer like anyone else but have the capacity to detach their minds completely from the nerve centers. In this way they might remember the pain only once or twice a day.

In South Kanara

One morning on a busy road near a village that some say was Panambur, the Master strode along at his usual rapid pace. Coming upon a pregnant woman, he stopped suddenly and squeezed her breasts. The woman did not resist but when outraged people began rushing toward him, Nityananda continued walking. He quickly outdistanced them, shouting that this time the child would live. The woman hurriedly told onlookers that her three previous children had died after their first breast feeding. Shortly thereafter, her baby was born and survived. A village delegation was organized to thank Nityananda, and the story spread.

This time Nityananda’s unconventional behavior became clarified after the fact, but it was not always the case. Another story says he came to the Pavanje River during the monsoon season. When the boatman refused to ferry him, the Master simply walked across.

When in 1953 someone asked him to explain the river incident, he said:

True, the Pavanje River was in flood when this one walked across and the boatman would not venture out. But there was no motive—it was just the mood of the moment. The only meaning was that the boatman was deprived of his half anna.

One must live in the world like common men. Once established in infinite consciousness, one becomes silent and, knowing all, goes about as if knowing nothing. Although he may be doing many things in several places, he outwardly appears as if he is simply a witness of life—like a spectator at the cinema. He is unaffected by events, whether pleasant or unpleasant. The ability to forget everything and remain detached is the highest state possible.

TRAINS IN MANGALORE

Nityananda loved trains. He traveled frequently by rail and even established his Kahangad ashram beside the tracks in 1925. When he was in Mangalore he would settle into one of the empty boxcars shunted aside at the station, and here devotees could find him.

One afternoon Mrs. Krishnabai, learning of his arrival, hurried off to receive darshan. She quickly returned home to greet a relative who had come for a visit. A sannyasi, he asked her to take him to see Nityananda the next day. Later, as they stepped down from the boxcar, Mrs. Krishnabai turned to the Master and said, “I came yesterday in such a hurry, never dreaming that I would also be able to return today.” But Nityananda replied, “Who are you to decide?”

He often rode the trains between Mangalore and Kanhangad. Once a railroad official who was new to the route ordered him to disembark for not having a ticket. As he made no sign to obey, the official forcibly removed him at Manjeshwar. Submitting to the rough handling, Nityananda proceeded to make himself comfortable on a station bench. But when its departure time came, the train didn’t move. Minutes ticked by and people waited expectantly. Finally, some passengers told the official that it was unwise to treat this particular sadhu so harshly. Devotees then took Nityananda on board and the train began moving. When it reached Kanhangad, however, it went past the station and stopped where his ashram currently stands. The Master descended wearing around his neck a garland made of hundreds of tickets.

He handed the garland to the same official, asking him to take as many as he wanted. Shamefaced, the man said it would not happen again. Nityananda then jumped the small ditch and strode off toward the jungle. Again the train would not move, and devotees ran after him for help. He retraced his steps, slapped the engine, and told it to get going. And the train did, going in reverse back to the station it had bypassed earlier.

Probably due to such incidents, Nityananda had free run of the trains. Engineers welcomed him into their engine cars and even blew a saluting whistle when passing his ashram, a custom still followed today. It is said that throughout the late 1920s the Master always had a punched ticket attached to the string of his loincloth

Early Days in Ganeshpuri

As word spread of Nityananda's arrival, villagers from surrounding areas began gathering around his hut in the evenings. A large pot of rice porridge, of which the Master would partake, always stood ready for them. Devotees were soon flocking to Ganeshpuri as well. To accomodate them, a building was constructed east of the hot spring tanks.

At first, due to a lack of potable water, visitors only stayed the day. However, once the old well was refurbished, sulfur water was used for everything. One particularly hot afternoon the Master offered a plate of rice with spicy pickle sauce to a visiting devotee. It so happened that the woman foudn sulfur water distasteful and declined the food, knowing that she would crave something to drink afterward. Nityananda again held out the plate to her, saying, "Don't be concerned. You will drink rain water." Venturing a look at the blue sky, she still ate nothing. Within minutes, however,a solitary cloud appeared overhead and rain poured down. The Master said, "Go and get your water," and she jumped up and collected rain water for both of them.

Devotees gathered late one evening on the west side of the ashram. Here Nityananda sat on a small ledge bordering a six-foot drop into the darkening fields behind him. Silence prevailed. Suddenly in the distance a pair of bright eyes appeared and, weaving its way slowly through the fields, a tiger came up to the ledge and stopped. The animal then rose lightly on its haunches and rested its forepaws on Nityananda’s shoulders. Calmly the Master reached up with his right hand and stroked the tiger’s head. Satisfied, the tiger jumped back down and disappeared into the night. Later Nityananda observed that as the vehicles of the Goddess Vajreshwari, tigers should be expected around her temple. He also said that wild beasts behave like lambs in the presence of enlightened beings.

Many stories tell of his uncanny ability to understand animals. In Udipi once he told its captors to release a certain caged bird because it constantly cursed them. Another time he reassured a frightened devotee that a nearby cobra was too busy chanting to harm anybody. Others remember a devotee who always came for darshan accompanied by his pet parrot. And in May 1944, Captain Hatengdi heard Nityananda say that a bird told him that it would rain in three days, and rain it did.

THE ATTORNEY FROM KERALA

Nityananda was tolerant of his devotees’ humanness; his actions indicated that one’s heart was free to turn to God only after the basic human needs were fulfilled. He made no demands, issued no commandments, and frequently concerned himself with their worldly comfort. In return, all he asked was that followers be prepared to receive that which he offered in such abundance.

This is the story of an attorney from the distant state of Kerala who regularly visited Ganeshpuri on weekends. As the years passed, however, the devotee felt keenly the loneliness of his unmarried state and finally announced he wanted a wife. Listening, Nityananda pointed to the surrounding throng and said, “Take one from here.” The prospective bridegroom instantly froze, concerned that his mention of a private problem had triggered a casual response. Bewildered, he sat as the people around him slowly dispersed until only one man remained, likewise from Kerala. Eyeing the attorney, he told Nityananda that he and his wife were having difficulty arranging a suitable match for their daughter. Nityananda pointed to his devotee.

Everything seemed settled until their families sent the potential couple’s horoscopes to a group of astrologers who unanimously pronounced the match unsuitable. When informed of this, Nityananda without a glance at the offending charts pointed out that a certain aspect nullified the negative signs correctly discerned by the astrologers. When this information was relayed to Kerala, the astrologers agreed, amazed at their failure to notice this vital detail, and the couple married.

IN LATER YEARS

The relationship between the spiritual and physical was sublimely simple—at least for Nityananda. When some devotees complained that travel conditions and old age hindered them from more frequent visits, he countered that his physical presence was unnecessary for their spiritual growth. "Devotees will find this one wherever they meet and talk. Fish are born, live and die in the holy Ganges without attaining liberation, but devotees have only to think of the guru." He had been saying this for years.

And when asked about the benefits of performing selfless serviced, the Master would reply, "Who wants it? God? Of course not—people only do it to get something in return. You should dutifully do your own work to the best of your ability without seeking a reward. That is the highest seva you can render. The only thing required for spiritual growth is a detachment from worldly pleasures. If you don't listen to this, you will fail in the end."

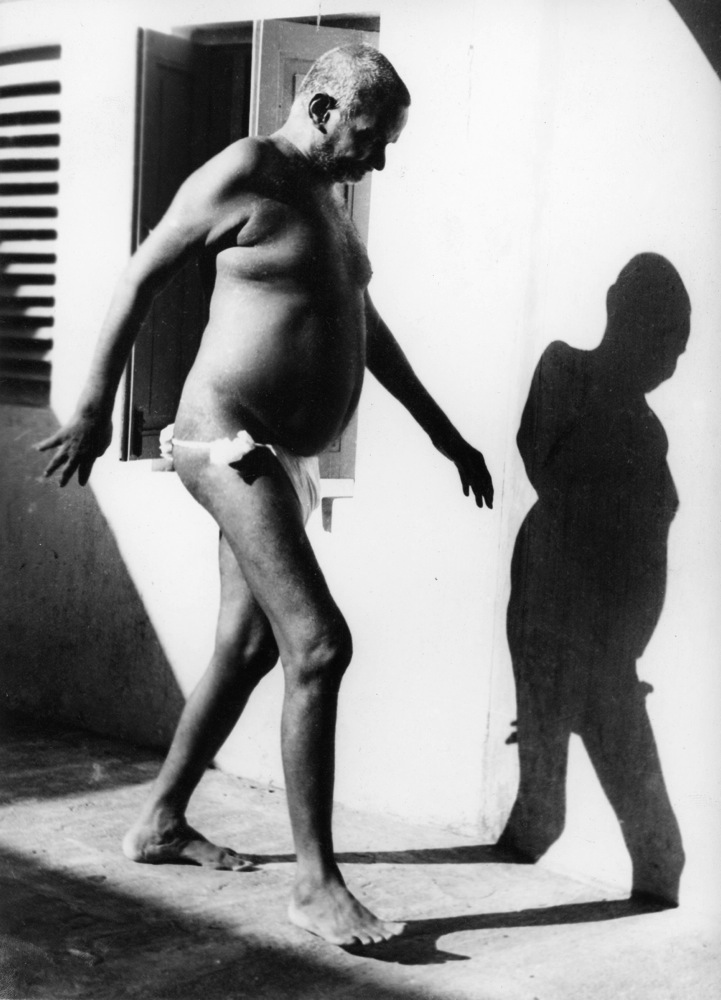

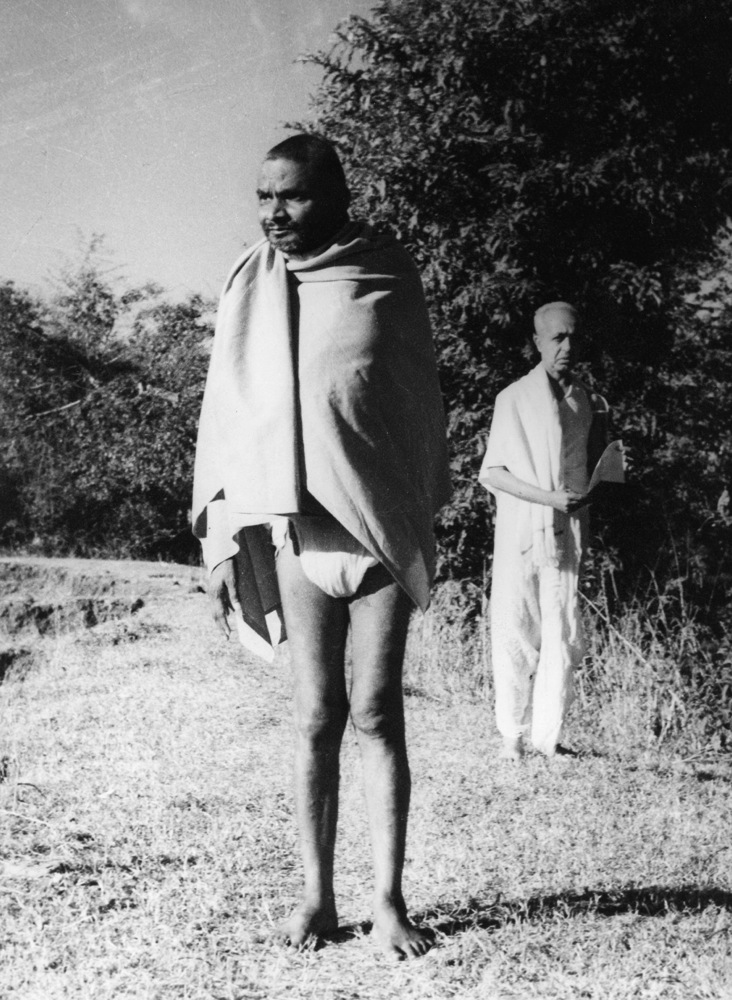

One day a devotee saw that Nityananda's feet were extremely swollen and asked about it. "People come here for some benefit," he told her, "and then leave their desires and difficulties at one's feet. While the Ocean of Divine Mercy washes away most of these tensions, a little is absorbed by this body—a body assumed only for their sake. "Nityananda's unconcern with his physical body was reflected in his devotees' constant awareness of it. And they were perplexed. By 1960, although he ate very little, his body had grown to huge proportions.

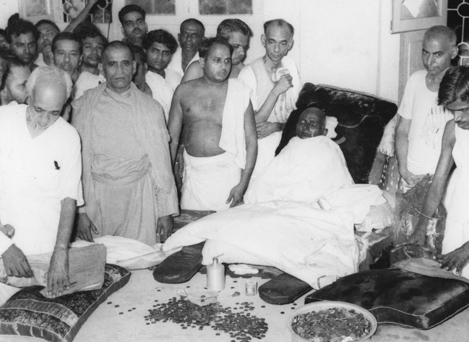

Alarmed, four devotees voiced their concern. The first was Sandow Shetty, who as a youth had been fond of gymnastics and feats of strength. The Master told him that his heaviness was due to lack of exercise. The second inquirer was Rao, who had suffered from malaria. Nityananda told him that his swollen stomach was the result of a malaria-induced enlarged spleen. The third devotee, a practitioner of pranayama breathing exercises, was told his size was a result of breath retention. Finally, Mrs. Muktabai came to him full of concern for his health and comfort. To her he said that the love of his devotees had settled around his gigantic belly. Regardless of cause, by the time Nityananda took mahasamadhi in August 1961 he was once again thin.

THE FINAL MONTHS

In his final months Nityananda complained that people only came to him for material gain. “What sort of grace is possible in such cases?” he would ask before adding, “They don’t need a guru—they need a soothsayer.” He called it an abuse of his physical presence, likening it to spiritual window shopping. Where was their spiritual aspiration? Why ask the ocean for a few fish when, with a little effort, one could have the priceless pearls on the ocean floor?

He spoke of the antarjnanis, realized beings who lived in the world and experienced pain like everyone else. The difference between them and the rest of humanity was their ability to detach their minds from their suffering. Once established in infinite consciousness, they became silent. And, while all-knowing, they lived as if knowing nothing; while manifesting simultaneously in unlikely places, they appeared idle. They viewed life as if it were a movie—from a state of detachment. For Nityananda, being detached from life’s circumstances, pleasant or otherwise, was the highest state. He was an antarjnani.

Let the mind, he said, be like a lotus leaf floating on the water, unaffected by its stem below and its flower above. While engagedin worldly pursuits, keep the mind untainted by desire and distraction. Keep the mind detached and faith in God firmly established in the lotus of the heart, never letting it be swayed by happiness or despair. Devotees will find themselves subjected to various tests, he said—tests of the mind, of the emotions, of the body. With every thought that pops into the mind, God is waiting for a person’s reaction. Therefore stay alert and detached. See everything as an opportunity to gain experience, to improve oneself, and to rise to a higher level. Desire alone causes suffering in this world. Humankind brings nothing into this world and takes nothing away from it.

Let one’s thoughts and actions reflect one’s words. This ashram’s practice is not about doing good deeds. This ashram’s practice is about learning to be detached. Anything else that happens does so automatically by the will of God—although this one will speak when somebody is genuinely interested.